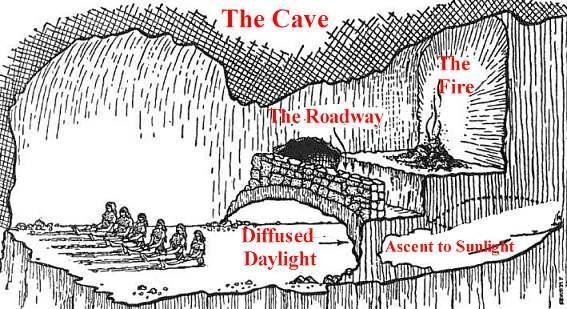

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Socrates tells Glaukon about an imagined scenario by way of illustrating his argument. In this scenario there are imagined people who are born, raised and who die in a cave. They are made to watch what amounts to a shadow-play on the back wall of the cave. They are not allowed to turn away from the wall, or even to look a each other. The shadows come from a fire, which illuminates people carrying things walking along a roadway.

Something like this:

The “meaning” of life

This cave society might develop theories and rules about the shapes of the shadows in order to decipher their meanings, predict their patterns, the order they come by, etc. They might even award honors to the best at this and congratulate each other on these skills.

The story goes that then one of these people is allowed to turn, to examine the cave behind them: the road, the people, the fire itself. This person may be blinded by the brightness of the “new world” and struggle to understand how all that was ever known has been a mere 2-D abstraction of reality. Or, may be even more bewildered when led out of the cave itself and allowed to behold the world outside, the searing sunlight! Given time, this person would, understand the meaning of the real world and how it translates to the shadows once watched.

Now enlightened, the person may feel bad for the cave people and go back, trying to bring the truth to them. But their eyes would be bad for the gloom of the cave. Now, the old peers would mock the enlightened person as insane for being so terrible at the shadow-interpretations, so delusional about the “true world” out there. What a crazy-person! It would take a long time and much effort before the two sides could see eye to eye, if they are able to at all.

The story goes further and makes some other perhaps questionable leaps of logic but so far, this is all we need.

The Struggle for Enlightenment

The purpose here is to illustrate the path of learning, from the darkness into the light, and the struggles of interaction between the enlightened and the ignorant. Yet even more than that, it provides a handy metaphor for the relationship between abstraction and reality. The shadows are incomplete but they are the shapes of real things. They are useful when we can’t see the “real” world that cast them.

In this frame of reference kata are not songs but they are shadows. (For reference, See the blog Kata are Songs) Something that is not like actual combat but more of an abstraction of combat. We examine the kata and are able to learn lessons from them in the safety of a laboratory environment (the cave). Where we won’t be trampled by the people carrying heavy objects down the road. Where we aren’t blinded by the light of the Sun.

Surely, to an experienced fighter who has never done karate, or one who has left kata far behind in their career, the choreographed moves of a kata may look trivial. And karate-ka, congratulating each other on a well executed kata, may appear silly. We should always keep in mind the distance between shadows and light, how they relate to each other and the ways in which both can inform the other. We must be mindful that expertise in both is difficult and dialogue can be fraught. An open mind is vital so that we can consider if the “crazy” person is delusional or perhaps has a different understanding of reality than us which can be valid and useful. Or if they have dabbled in the wrong kinds of chemicals.

Thank you

Francisco Berro