Research is never a straight line; my experience with AP Research showed me just how winding the path toward progress can be. It all began one fateful day during a conversation with my father. I remarked that it feels as if people are actively opposing fights for equality. This baffled me, I couldn’t understand why anyone wouldn’t want the lives of others to be improved, especially when it had no negative impact on their own. That moment sparked my research project. Formed from genuine curiosity and a desire for change, I sought to explain this phenomenon.

Not Enough Resources?

At first, I thought the answer would be simple: people don’t want to help others because it takes resources away from them. But I quickly realized how wrong I was. There are more than enough resources to go around. Like WAYYYY more. However, when 10% of people control 90% of the world’s wealth, the problem isn’t economic, it’s systemic and psychological.

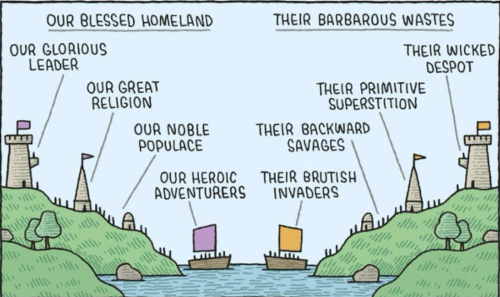

My first stop on this path was Us vs. Them psychology. Henri Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory suggests that people seek to enhance their self-esteem by identifying with in-groups and differentiating from out-groups. This differentiation can lead to favoritism, prejudice, and stereotyping as people favor those who belong to their own group. I realized that if people don’t view others as equal—or worse, if they see other groups as direct threats to their safety—progress will stall. I wondered if this resistance was rooted in our evolutionary biology. I thought back to biology class, where we studied early humans competing with Neanderthals. If another group succeeded, it could mean fewer resources and even death for your own group. When survival depended on out-competing others, the brain evolved to perceive outsiders as threats. That wiring persists today, even when the stakes are no longer life or death.

The culprit: The amygdala?

The implicit bias associated with this disparity is directly tied to the amygdala, one of the oldest structures within the human brain. As Joseph LeDoux explains, implicit bias once served as a survival mechanism: early humans relied on in-group favoritism to ensure trust and protection, while suspicion of outsiders reduced risk. Outsiders often posed real threats—competition for food, territory, or mates—and the amygdala evolved to trigger vigilance when encountering unfamiliar individuals. But today, those same circuits misfire. Neuro imaging studies show stronger amygdala responses to out-group faces even in neutral contexts, while stress hormones like cortisol suppress the prefrontal cortex, impairing rational evaluation. What once kept us alive now fuels prejudice and division.

Since doing this research, I’ve begun to notice Us vs Them psychology everywhere in my daily life. I see it when watching the news with my dad, where political debates often frame issues as battles between opposing sides rather than opportunities for collaboration. I see it in subtle moments too, like a woman clutching her purse tighter while walking past a Black man downtown. These experiences remind me that the theories I studied are not abstract; they are lived realities that shape how people interact every day. Recognizing these patterns has made me more empathetic, but also more determined to find solutions.

Hope for Understanding

This realization re-framed my question: now that I knew why people thought and acted the way they did, what could be done about it? If resistance to equality is not just ideological but biological, then solutions must address both mind and environment. Neuroscience offers hope. Fear circuits are plastic; they can be rewired. Research shows that positive inter-group contact reduces amygdala reactivity over time, while re-framing equality as opportunity rather than loss lessens perceived threat. Practices like mindfulness strengthen prefrontal regulation, allowing people to override anxiety-driven bias. Education itself—teaching people about the neuroscience of fear—helps individuals recognize possibly defensive reactions and re-frame them.

Managing this winding path was not easy. At times I felt overwhelmed by the sheer complexity of the problem. Each new discipline I encountered—psychology, biology, neuroscience, sociology—added layers I hadn’t anticipated. But I learned to embrace uncertainty rather than fear it. I sought mentorship when I hit dead ends, re-framed setbacks as opportunities to dig deeper, and leaned into curiosity as my compass. What began as frustration transformed into resilience, teaching me that progress often requires patience, persistence, and openness to perspectives beyond your own.

My research took much longer and crossed more fields than I originally envisioned. Yet this interweaving strengthened my overall understanding and showed me that to truly solve a problem—or even begin scratching the surface of a large societal issue—you must incorporate many different fields. The world isn’t siloed, and by isolating our understanding to only one discipline, the truth will never be fully understood. Just as increasing diversity among people groups is a solution to systemic inequality, diversity of thought is the solution to tackling the world’s biggest problems.

The Path Forward

In conclusion, my path was much more complex than point A to point B, but it gave me a deeper understanding of why resistance to equality persists and how we might overcome it. Geometry may favor straight lines, but my AP Research journey taught me that the winding path often reveals deeper truths. It opened my eyes to the necessity of nuanced thought: the ability to embrace complexity, integrate disciplines, and design solutions that honor both biology and society. That is the kind of thinking our world needs. Not just to understand resistance, but to build inclusive futures where fear no longer divides us, and equality is seen not as threat, but as opportunity.

Thank you for your time.

ZaHir Covington

Other Thoughts from our Blog:

Fear: Why does it hold us back?

Don’t Be the Pink Tire

Frame of Reference

Shadows and Light